The year I lost

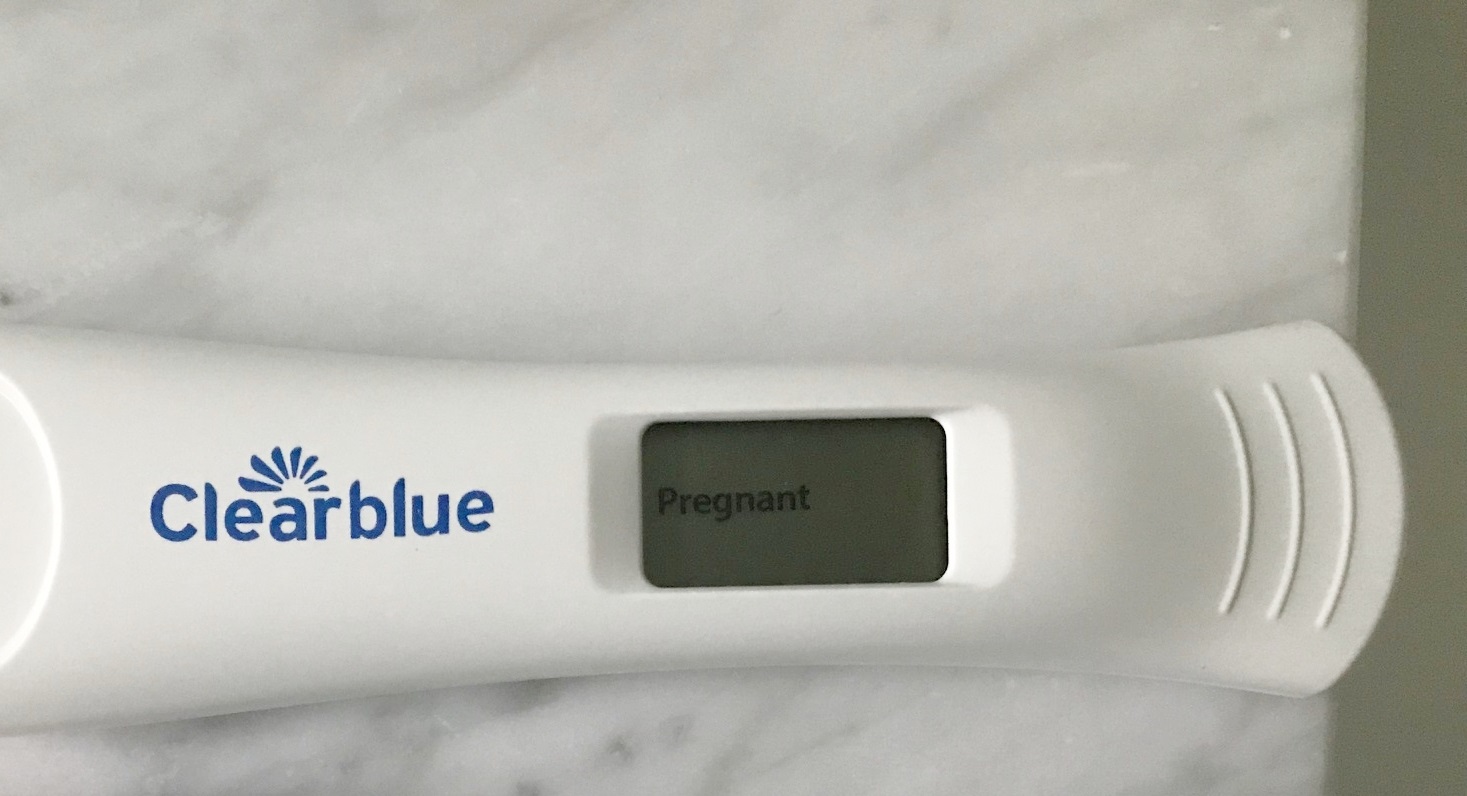

So I’m 37 weeks pregnant and I still have not announced my pregnancy on my personal social media accounts. That’s because I had five miscarriages last year, and I’ve held my breath for 37 weeks. In fact, I’m still holding it. For a year, I felt like everything was overshadowed by these losses. I was distracted from my academic career, and my family.

My first loss was the hardest, because it was most unexpected (after two normal pregnancies and no history of loss) and because I was almost 12 weeks along.

I could hardly contain my excitement, and told my best friends and immediate family just after we had our first ultrasound. We also told our other children (3 and 5 at the time) after we had our first ultrasound around 7 weeks and everything looked normal.

There was a strong heartbeat at 7 weeks, and everything seemed okay until I went to my 11 week appointment and I found out there was no longer a heartbeat.

Though I have struggled with whether to tell friends and family members about my losses, ultimately, I think this is an opportunity to normalize pregnancy loss. As I have come to realize, early pregnancy loss is relatively common among women (>3 million cases/year in the US). But it’s a taboo topic and many women tend to suffer in silence, feeling alone. For those reading who think this is way too personal to write about, ask why that is? Why should we not talk about something that happens to so many of women (15-25% of known pregnancies)? Other estimates range as high as 30-50% if you count some of the very early pregnancies that may occur before women ever take a pregnancy test or confirm a pregnancy. I find it surprising that much of society is totally oblivious to this problem. In a national survey of male and female participants 18-69 years of age representing 49 states in the U.S., the majority believed that <5% of women experience miscarriage, and there were widespread misconceptions about miscarriage. There is an aura of shame and humiliation around miscarriage, perhaps because many women blame themselves for what is most likely entirely beyond their control. I certainly did. The term “miscarriage” implies the pregnancy wasn’t carried appropriately and the term itself can be damaging to the mother carrying the pregnancy. And calling it “abortion” (i.e. spontaneous abortion) also has some heavy emotional baggage to it as well.

For me, I think back to every little event during my pregnancy and wonder what I did wrong. Was it that half glass of wine I drank on vacation? Could it have been the three bites of sushi I ate? What if I unknowingly ate some unpasteurized cheese? I had a few flights during early pregnancy, maybe that was the culprit? I was really nervous about telling my work colleagues since I had recently accepted a big promotion, and I wonder if there was some level of work stress there that could have resulted in this loss. Maybe I exercised too hard on my run, was too stressed at work, or slept on the wrong side, or GOD I DON'T KNOW, THE POTENTIAL FOR FAULT IS ENDLESS!!!

This is a subject that is really hard to research, since there really is no good measure for the denominator of all pregnancies -- some pregnancies are unintended and early losses may not be known, and not all women report an early loss at a doctor's office. But research suggests that the majority (~60%) of early pregnancy losses are due to chromosomal abnormalities, i.e., it likely wasn't my fault. And with advancing maternal age, losses are even more common (for me, my first loss occurred only a month after my 35th birthday so loss, especially after two totally normal pregnancies and no prior issues, was not on my radar).

One of the largest studies to date was conducted in Denmark and examined >90,000 pregnancies and examined the potentially modifiable risk factors for miscarriage (defined as loss < 22 weeks gestation). The researchers found that the potentially modifiable pre-pregnant risk factors associated with higher miscarriage risk included: age 30 years+ at conception, underweight, and obesity. Modifiable risk factors during pregnancy included alcohol consumption, lifting of >20 kg daily, and working at night (hoping this latter one means night shift work on your feet, not the type of “work” I do at night like writing papers/grants and being kept up by sick kids!!).

Despite this, the emotional burden of a early pregnancy loss lasts many months, and studies have found that the level of grief following a miscarriage is similar to that of losing a close relative. It’s easier for me to look back NOW, while I’m carrying what seems to be a healthy baby that will be born at full-term, and say that it wasn’t that big of a deal and everything is fine. But in that year (plus) that I lost, with the ups and downs of hormones, it was a lot harder to see any silver lining or maintain any sense of hope.

In that same survey, about half of women felt that they had not received adequate emotional support from their medical community about their pregnancy loss. I too do not think I got support from my medical community. I had a very insensitive doctor who, when I went in to my 11 week ultrasound, told the medical student observing that there was something wrong with the baby before he told me (I was in the room too and of course overheard there was a problem!). His only reassuring words were: "Sometimes this happens; you can try again soon." These words provided me no comfort, as he ushered me to a scheduler to make an appointment for the surgical procedure to remove (or “abort” as he said) the fetus as I tried to hold back tears and process what I had to do next. I was alone at this appointment, and felt there was a missed opportunity for my care provider to provide at least a bit more reassurance and comfort. I didn’t know where else to turn for answers, but I poured over the medical literature and obsessed about every potential cause of loss, and read all of the statistics about recurrent loss. I was somewhat comforted by the literature around recurrent miscarriage, and that only 5% of couples will experience another consecutive miscarriage. Unfortunately I fell into that category (again and again and again).

This is why talking about pregnancy loss and normalizing it might help women. Because despite the lack of emotional support I got from my medical community, my friends and family that I did tell about my losses helped make me feel better and have at least tried to convince me that it was not my fault. I also found it comforting to talk to other friends who had experienced early pregnancy loss, and was surprised at how many had experienced it but hadn’t talked about it with anyone.

I’ve been struggling considering what I should do to better support women who may be having difficulty trying to conceive or who experienced a pregnancy loss, and here are a few thoughts to get the conversation started:

1. If someone does tell you about their pregnancy loss, react with kindess. You can help to remove the stigma of this discussion about miscarriage and loss in our society by responding rather than ignoring or asking why someone is talking about such a personal topic. Not sure what to say to someone that experienced a pregnancy loss may share this with you? Just give a heartfelt "I'm so sorry" and “this is not your fault.” It's not helpful at all to say "you can try again soon," or "but you already have two kids." It’s also not helpful to say “at least the loss happened early”, “at least you know you can get pregnant”, etc. While well intentioned, these words only made me feel worse. Acknowledging the grief is okay. Even if it has been a few weeks or months, if your friend/loved one had told you about the loss in the first place, it’s still okay to mention it, and ask how the person is doing. This person is most likely still thinking about the loss on a daily (hourly?) basis, and might want to hear some encouraging words and not think you have forgotten what they are going through.

2. If someone has NOT offered you any information, never ask a woman if they are pregnant unless they are so obviously showing there is literally NO other explanation. I was showing by 6 weeks, and had several people who weren’t very close to me ask me just after my loss if I was pregnant and it was a VERY AWKWARD conversation. Just use this meme that has been going around the internet for awhile as a guide…

3. Similarly, it's probably not a good idea to ask someone if they are going to have kids anytime soon. This may be a really difficult question for someone to answer if they have experienced losses or have been trying to conceive for years with difficulty. I have been trying conceive for nearly two years, but there are many women who have been struggling for many more years. Unless it's a really good friend, it’s probably best to just let the person offer this information to you first. I have certainly made this mistake in the past (I’m sorry!) and now I know better.

4. Change the language around “miscarriage”. The term has a negative connotation and implies a fault in the one carrying the pregnancy. Early pregnancy loss may be a better way to describe this. We need to change the culture around this conversation.

5. Change the acceptability around telling friends/family members about pregnancy before the first trimester. The long-standing advice in our culture has been to keep pregnancy news to yourself until after the first trimester, when the risk of miscarriage is <2% (I obsessively checked this miscarriage risk calculator throughout my pregnancy!). Yes, it is really hard to tell people about exciting news around pregnancy and then have to tell them about the loss, but I think if we consider telling everyone who we would want to support us during a time of loss, those should be the ones you tell as soon as you are comfortable with this information. I had friends ask if I regretted telling my older children about my loss, and the answer is no. I felt much more supported when I was honest - my kids knew why I was upset, and could actually offer some comfort to me. My daughter would check in on me frequently and ask me every week if I was still sad about the baby. And she told me a few weeks ago that throughout this whole pregnancy she has been wishing (on her eyelashes, her dandelion flowers, and any other opportunity she has) that this baby is okay. And my friends who I told have been incredibly supportive as well.

6. Better support academic mamas who experience pregnancy loss. Finally, acknowledging my privilege as a full-time employed academic mama, with a lot of flexibility in my job, I was able to take a few days off here and there when I experienced these pregnancy losses. Two of them required surgery. It wasn’t enough time though and I didn’t take any formal leave. I can’t imagine how difficult it is for those who do not have flexibility and cannot take any time off to heal (both physically and emotionally). Given the number of losses I had, on several occasions I had to continue work while taking little time off (e.g., traveling, lecturing, teaching) and this was difficult. I recall in the middle of one of these losses having to listen to someone on my team complain directly to me about how I needed to do a better job of being available and I wished I could have explained. So if you are a boss, have some compassion and provide flexibility and time off when needed. If you are another academic colleague to someone who has had a loss, have some understanding!

7. Providing an environment where trainees and our young females feel that they can have children whenever it is best for themselves. When I was early in my own academic career, and knew I wanted to plan to have children, I felt that I must first prove myself academically before I took time to have a child. So, I told myself I wouldn’t have children until I got my first grant. No one put that pressure on me explicitly and it was certainly more internally driven, but I know from colleagues and friends, many of whom are physicians whose training persisted through their mid 30s also delayed having children. Then, many of them were in the situation where they had trouble conceiving, or their pregnancy loss rates were higher. This is a another problem that must be addressed through prevention. In an ideal academic environment, a woman’s choice on when she decides to have a family (and how many children she wants, or if she decides she does not want any) should be supported no matter the timing. Flexible leave policies and back-up care options for when children are sick for graduate students and post-doctoral fellows can also go a long way to make sure students or younger females feel supported in their desire to build a family WHILE also working on their academic career.

For those who have experienced pregnancy loss, what did you find helpful from friends, families, or colleagues? Did your academic work suffer or were you supported?